Commonwealth Supply Chain Advisors recently published a ground-breaking white-paper titled, “Beating Murphy’s Law in Warehouse Automation Projects.” The full paper examines a number of the reasons why automation projects fail to meet expectations, and what companies can do to beat Murphy’s Law. This blog is ninth in an ongoing series on “Beating Murphy’s Law in Warehouse Automation Projects.

The best designs and project plans can still fail in the hands of the wrong vendors implementing the project. Companies do well to conduct a thorough vendor selection process to ensure that the companies they partner with are those best equipped to meet their needs.

The best designs and project plans can still fail in the hands of the wrong vendors implementing the project. Companies do well to conduct a thorough vendor selection process to ensure that the companies they partner with are those best equipped to meet their needs.

Some key mistakes companies often make when it comes to vendor selection include:

- Love at first sight: Some companies irrationally latch on to certain technologies, which they may have seen at trade shows or site tours, believing it must be the right choice for their company absent of any objective evidence. Many of the forms of warehouse automation in use today can be impressive to observe and have in fact transformed many operations for the better. But, as pointed out in earlier sections, each distribution center is a unique “snowflake” with specific requirements that differ from other sites. Technology that works well in one distribution center may be the wrong choice for another facility – even one in the same industry. There is no substitute for an objective design process based on empirical data modeling and broad perspective on the solutions that actually work in the real world.

- The lowest price wins: Companies are right to seek competitive pricing from their vendor partners, but many make the mistake of prioritizing price above all else. This may be a valid strategy for less automated solutions, such as static storage equipment and vehicle-based picking systems, where the products in question have become commoditized. In these cases, product designs are often fairly standard and minimal custom-engineering must take place. Simpler equipment can often be well-described in detailed functional specifications, and if bidders adhere to these specifications, then a strong case can be made that the lowest-price vendor should be awarded the contract. However, for more complex systems, the lowest price vendor may not always be the best choice. When systems are highly complex and difficult to fully describe in a written specification, then there is often a large potential for vendors to cut corners in ways that are not initially evident. Additionally, the success of complex automated systems often lies in the ability of the vendor to understand the unique operational requirements and engineer a custom solution for the client. Often, the low-price bidder may not have invested as heavily in their engineering staff or quoted the same number of man-hours as other bidders who have taken a more thorough approach. Many times, by over-emphasizing price as a decision criterion, companies unwittingly pressure even responsible vendors to cut corners and omit key design features, which may prove critical to the success of the system. Often, a low price that seems too good to be true can mean the vendor has under-staffed the project, and the customer can be forced to take on a larger share of project implementation responsibilities than they are able to easily handle. Key implementation responsibilities may be forced on the customer’s internal staff, who may or may not be prepared to play these enhanced roles. Companies should instead take a balanced view where system price is one of several design criteria, and not necessarily the most important one.

- The familiar company wins: Many companies make the mistake of using a vendor that may be familiar to them, but not well qualified to undertake the present project. Certainly, there is value to working with partners who have a solid, proven track record of executing on past projects. However, companies do well to ask themselves whether they have taken an honest look at the “familiar” company’s qualifications and track record of designing and implementing the specific technology in question, for the current initiative.

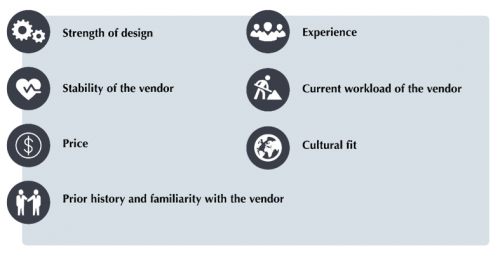

Companies implementing warehouse automation should instead take a well-rounded approach and conduct a thorough request for proposal (RFP) process that evaluates the following criteria:

To read Commonwealth’s complete white-paper titled, Beating Murphy’s Law in Warehouse Automation Projects, click here.